This is a slightly edited version of a talk I did as part of De-platformization, Ethics and Alternative Social Media at Dispaly, Prague on the 25th September 2020. A lot of what I argue for at the end—supporting online social infrastructure though offline institutions—was demonstrated by the historical examples presented by Dušan Barok and current work Lídia Pereira & Christina Cochior from Varia, Rotterdam. A recording of the whole event will be available at artycok.tv very soon. Thanks to Hana Janečková, Nikola Brabcová and Michal Klodner for the invitation.

I recently re-joined Twitter, and so far I would say that it’s been a terrible mistake. I re-joined for ‘professional reasons’, which means that it has just enough connection to what I’m meant to be doing to feel like I’m doing something—when obviously it’s just a great way of doing nothing—with just the right level of micro-stimulation to never drop below my threshold of boredom.

Previously I had been using Twitter but using it wrong. My account got blocked for trying to verify with a fake phone number and so all I could do was go to specific people's profiles and see what they’d posted since the last time I’d looked, limiting me mostly to the 5-6 accounts who’s handles I’d committed to memory. Interestingly this is one of the suggestions that the artist Olia Lialina makes for misusing the internet, or rather reviving forms of use from a previous internet ages, before the walled gardens of the platform started telling us how to do the internet right, and shutting us out if we kept doing it wrong.

"For instance, you can decide not to use Twitter at all and instead inform the world about your breakfast through your own website. You can use Live Journal as if it is Twitter, you can use Twitter as Twitter, but instead of following people, visit their profiles as you’d visit a homepage" (Olia Lialina, Turing Complete User, 2012).

So today I want to talk about some different ways of using the internet, and although I don’t want to get too nostalgic I am going to look at some historical examples of a time when we, or rather I, used the internet differently. The reason I want to do this is to try and move away from talking about how and why the centralising, monopolistic platforms of social media are bad—and they are of course really bad—to talk about how we, as users, are a big part of the problem and if we might not be getting the internet that we deserve.

So, it’s the year 2000, I’m 13 years old, growing up in a regional capital with a 28k modem and, like all 13 year old boys, I’m interested in 3 things: Apple computers, the occult and spoons.

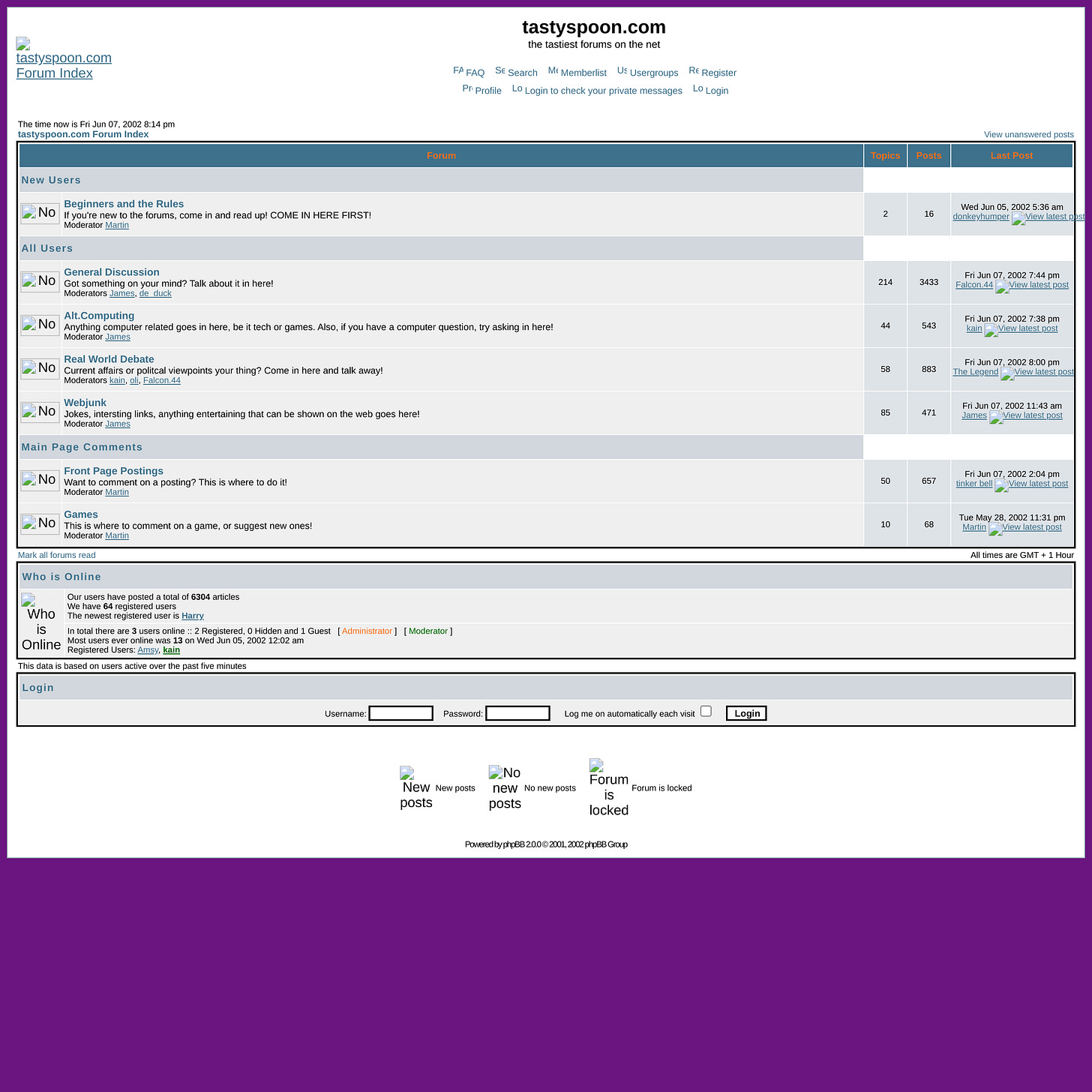

As you might have noticed, despite their different subjects, these three websites where I spent time as a teenager look surprisingly similar. That’s because it’s the era of UBB, ultimate bulletin board a piece Perl-based forum software launched in 1997.

These three bulletin boards where I spent my online time as a teenager are examples of decentralised social media. What happened in these places? The things that we associate with the internet before the rise of the platforms. People from different place in the world came together around a specific interest to discuss that interest and then, most likely things unrelated to that topic. And they did this anonymously, or rather privately, with privacy understood as what "enables a decision as to where one wants to be on the spectrum between secrecy and transparency in each situation” (Shoshana Zuboff, Big Other, 2015) or the right to decide how much information to reveal, when and to who.

Also, I think very importantly, though they used the some software, they boards weren’t federated. There was no link between my activity on Ai, wicca.nu and Tasty Spoon. I could be different people on each, just as I could be a different person offline.

Tasty Spoon was a bit different. It wasn’t actually a specialist interest spoons forum. It was run by someone I knew, and was largely for people in a couple of high schools in the same city who knew at least a few of the other people there but, to my memory, there was still a split between online and IRL. It wasn’t a digitisation of existing social relations or offline conversation. The things that happened there were quite specific.

The result of this unfederated decentralisation—the same software running in different places, unconnected—was that there was no network effect, the idea that “the more people who use them, the more useful [networks] are to more people." But there’s an underlying assumption in this—what’s called Metcalf’s Law—that there’s no limit to the value of more connections. This, would argue, is not true and it’s not true for two, related, reasons.

The first is what we’d call the mode of address—how we talk, based on who we think we’re talking to. Unlike the forum, where everything is posted with the expectation of a reply, on social media platforms the default mode of address is public broadcast: “What’s happening?” “What’s on your mind?” “What’s on your mind, John?” And if I want to know what’s happening, or what’s on various people’s minds, then I’ll go to Twitter or Facebook and what we find there is largely a mixture of people focus grouping their personality—seeing which of the things on their mind get the most attention—and commenting on things that are happening outside of or elsewhere in the network. And this is not necessarily bad but it’s not actually very social. Instead what you get is a form of interaction that’s less like a conversation and more like this…

Richard Seymore, in his very good book about social media The Twittering Machine suggests one of the reasons people are drawn to social media is a the Drama. And while this is surely true, I think it’s important that our participation is rarely of any consequence. We’re usually quite passive bystanders, maybe liking, maybe retweeting, maybe adding a “This!” comment to something we think everyone who follows us should know we agree with. And unlike in that clip from Fahrenheit 451, we don’t need to call up our friends the next day to ask if they saw us, because surely if they’d seen it, and if they were really our friends, they would have smashed that like button straight away.

But just like in that clip all responses being of equal value. It is the connections made by content, rather than its meaning, that is the measure of its value. Or rather it is the connections that are meaningful, rather than what’s actually happening, or what’s on your mind. Rather than necessarily hoping for a reply, a conversation, we judge the value of our output on social media how many people have seen it, how many people have acknowledged it. This is platform logic, it’s the logic that comes from advertising, and because these platforms are designed so as to make them more useful to advertisers—advertisers, like us, are also users of these platforms—the kind of use that works best on social media platforms is continual brand building and self-promotion. Making connections—by liking, sharing and following—to things that are on-brand and criticising, mocking, or blocking things that are off-brand.

This leads to the second limit that we encounter in the network effect, the filter bubble. The filter bubble is a concept which is largely bullshit and generally misunderstands the problem, which is that we need more, better, stronger filter bubbles. While the social media platforms are very good at filtering, they are actually very bad at the bubbling. I can decide who I follow, and I can even decide who follows me, but I have no influence on what or how any of my followers filter content and I can have only a very limited idea of what they’re looking at and on what basis we could begin a conversation. Bubbles, as they did exist in the decentralised world of UBB, meant that once you found your way inside, you knew that you saw the same thing as everyone else and everyone else saw the same thing as you. You knew you had a shared basis on which to start a conversation and if you wanted to start a conversation, it might be a good idea to start with a question and engage with the content of the answers, rather than the numbers your thread was doing. There was still of course metrics, you’re thread could rise to the top or the page—and this encouraged trolling and shitposting in its own way—but you needed replies, but just views, likes or boosts.

Of course forums still exist. We have Discord and Reddit, though these are centralised, platform models of forums, and we have the chans—4chan, 8chan, MumsNet—famously anonymous, isolated from the real world, and hugely culturally and politically influential: lolcats, anonymous, QAnon, transphobia, racist and misogynistic terrorism. My dad runs a cycling forum, which has also been used for political organising, with campaigns to increase funding for cycling and reduce speed limits.

But the bubbled, thread-based forum has largely been replaced by the open feed-based platform, with the endless scroll and algorithmically curated timeline always giving us just a little more of what we want, without us having to ask. Richard Seymore suggest that we understand social media using an addiction model—that we’re social media users in the same way that we might be users of crack—but argues that we should worry less about what social media is distracting us with—the thrill of online drama, or the gamble on a post's like to comment ratio—and more about what its distracting us from, the things in life that we don’t want to have to do or think about or deal with, including social anxiety and loneliness. It’s a social model of social media addiction, but he’s also keen point to out that the things we used to use to deal with social anxiety, namely cigarettes and alcohol, weren’t really very good for us either.

There’s another reason that I think the forum fell and the platform rose, and that’s a question of institutions. Wicca.nu was attached to the ancient format of the hand-built specialist interest information site of a kind I don’t really think exists any more. It was a project of one person, a 18 year old Canadian who maintained and hosted the forum that outlived the site but ended until 2007. Tasty Spoon was also the project of one person who as went on to train a church minister, which I think tells you something about the kind of person who want to run forums. By 2008 it was dead. The AppleInsider forum was attached to the larger, professional tech news website. It still exists, but is used largely for commenting on news articles posted by the main site, with very little off topic discussion.

Decentralised social media is often dependent on one person continuing to think that it’s worth their time and money. My dad said his hosting and domain cost him about £60/year and that most of the work involves filtering out spambot user registrations. Facebook might be hell, but it’s free and it’s not going to go offline anytime soon. Of course for Facebook and Twitter staying online is question on commercial value, not social usefulness. If we want sustainable, decentralised social media that values the things that it enables, and not just because they might be valuable to advertise, then they need to be based not on the commitment of one person, or even on a network of social relations, but instead be supported by institutions.

Institutions are, if nothing else, systems and structures that can sustain identity. While he curated feeds of social media are very good at allowing users to cultivate an individual identity—a unique username and unique password, behind which we keep our individual selection of what we want to see and how we want to be seen—this is at the expense of a group or collective identity, something that I can identify with and an identity I can share with others. AppleInsider and Wicca.nu were part of my identity, part of forming my identity, with other people but I could also feel that to some extent I was part of forming the identities of these spaces. No one identifies with Facebook or Twitter, or if they do it’s meaningless because that identity can’t be shared. Everyone’s experience of Facebook and Twitter is, by design, different.

Facebook of course does have a sustainable identity, one that’s maintained by people in offices (and at home) all over the world being paid to keep everything working and by shareholders expecting it to work in a way that makes them money. If we want small-scale decentralised social media it doesn’t just need to be useful, or entertaining to a user base, to be sustainable it also needs to have a stabilising relationship between its own identity and the identity of its users. Its coherence and identity need to be maintained by a coherent, sustainable institution. Now, in theory, the users could institute themselves. This is a very high cost, and so the value compared to the free-to-use, commercial platforms would have to be very high. Much better, I would suggest, is that existing institutions that already have a sustainable organisational structure support online communities that they find mutually beneficial.

The current model of social media that we have, where we just advertise ourselves to each other, is by its nature just a very powerful distraction from a profoundly anti-social world. Having a stable place from which we can envision and identify with a world that is less anti-social, and organise to make a world more like the vision, seems to me essential. The practise of building and maintaining institutional supports for social interactions would, to my mind, not just be a model for how to make wider political and social change, but the first step of doing it.